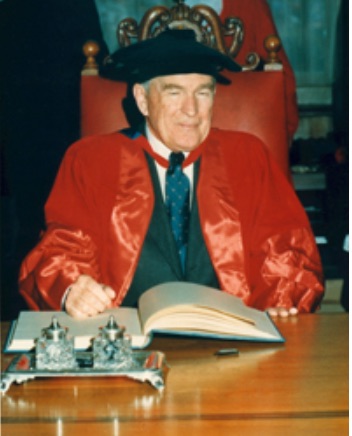

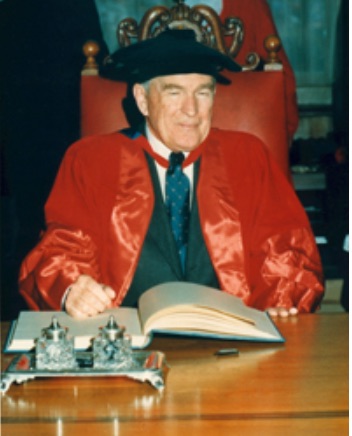

1988 - William C. ("Bill") Carter

Mr. Chancellor,

Computers are fascinating. Perhaps that is because there is something human about them. They can work out all sorts of things but they seem to fail with those things in the world that just don't add up. Often they inspire awe, especially when they threaten to replace us. Indeed, in a way they are superhuman because, given a chance, they make errors much bigger than those of which we are capable. So, it is with special anticipation that I present to you William Carter who has made it his life's work to stop computers making mistakes, or faults, as he would call them.

How William Carter came to spend his life working on the subject of fault-tolerant computing, it is now impossible to tell. His life betrays no evidence of fault of any kind. Trained as a mathematician at Harvard University and at Balliol College, Oxford, where he was a Rhodes Scholar, he immediately turned to computing in 1947. The best computing facilities in the United States at the time were to be found at the US Armed Forces, Aberdeen Proving Ground, where the problems were those of statistics. There William Carter stayed until 1952, while acting as Instructor at both the University of Maryland and Johns Hopkins University.

The reliability of computers at that time depended on component technology and simplicity of design or protective redundancy - a kind of duplication. If one system failed, the second immediately 'retried' the operation. Such computers were slow but in 1948 there was the promise of a new fast electronic computer called ENIAC, one of a long series of acronymous pieces of computer hardware that punctuate William Carter's working life. ENIAC and a modification of it were a great advance and constituted the beginning of computing as it is understood today.

Modern research must be carried out in teams; this is particularly the case for those interested in fault-finding. So, William Carter got married. His wife Ginnie, whom he met at a, not the, Boston tea party, was also a computer expert.

Her work in Washington at the time was so secret that there could be no talking shop on their brief honeymoon. This had to be brought to an end when, after installing his new wife in the matrimonial home, William Carter replaced the elevated sweetness of the honeymoon with the profundity of the Honeywell, by installing their first Datamatic 1000 computer.

William Carter is an enthusiastic fisherman. His homes on Bailey Island in Maine, the state in which he was born, and that on Tortola, one of the British Caribbean islands, afford ideal fishing. So, fishing around for the next step in fault-free computing, he decided to resign from Honeywell to work for the US Government in Washington. Security clearance took so long to come through that impending penury led him, in 1959, to work for IBM instead. He still regards this as the best move he ever made and he stayed with IBM until retirement in 1986. Most of the time there was spent on his first love in fault-free computing and on this subject he has made contributions of the first importance.

Those of us who rely directly or indirectly on computers, and that means most of us, owe a debt to William Carter. With reliability comes safety and so he has enhanced our lives.

William Carter has chaired countless professional and technical committees, usually ensuring that they meet in what is conventionally described as 'nice places'. He has been much honoured for his contributions to computing and on his retirement a special conference was held, the proceedings of which were presented to him as a Festschrift.

William Carter knows Britain well. While working at IBM he frequently came to visit their laboratories near Winchester. He has also made a notable contribution as a lecturer during the Newcastle three-week advanced computing course, which he remembers particularly well for its special welcome of almost continuous rain but his enthusiasm for us remains undampened.

Mr Chancellor, when we speak of computing we mean speed and reliability. Without William Carter's contribution neither would have been possible. I ask you, therefore, to confer on him the degree of Doctor of Science honoris causa.

Professor Max Sussman